While planning this blog, I had a really great idea to do a “Top Five Things I Learned From Leuven” post, with cute little anecdotes illustrating how I’ve changed and what challenges I’ve faced working in this environment. But as I started brainstorming ideas, I realised that everything I was thinking of all fell under the same umbrella, and could be summed up nicely in one sentence:

It’s okay to feel like you have no idea what you’re doing.From the moment I stepped off the plane and had to search for my luggage, find which train headed to Leuven from signs in a new language, and make my way to our dorm, I was bewildered, confused, and unsure every step of the way - all before even getting to work! Perhaps where I felt it most poignantly was in my second week of work, when I analysed waveguides on my own for the first time. Though I’d used the system several times before, I was still second-guessing myself the entire time getting the laser aligned and the microscope ready. The whole time I wondered to myself, why are they letting me be in charge of this (very expensive) equipment all by myself, when I haven’t even been working for a full week?

Moments like this were a common occurrence: finding the right train to get to Brussels, buying food without understanding what was in it, trying to navigate a completely new city, working on projects at IMEC that were completely new from what I’ve done at Hopkins. I was completely, totally out of my comfort zone.

But from this, I learned. I learned that you have to trust yourself, and trust the skills you didn’t know you had. Though I had never worked with waveguides or optical fibres, within a couple weeks I could analyse entire sets in an hour or two, more efficiently than anyone expected. Though I’d never worked with cardiac cells or micropatterned chips, I worked entirely independently for two weeks while my supervisor was at a conference in the States, and was able to get a lot of good data and refine our protocol along the way. In high school and at Hopkins I’d learned the basics - how to use a microscope, how to culture cells, how the cells actually work, how to analyse and present data. And for the first time, it was up to me to use these skills without anyone looking over my shoulder, and make something meaningful using them. “What am I doing?” turned into “Yeah, I got this,” and I’ve come out of it much more confident in my skills, both in what I’ve been used to doing, and my ability to adapt to new situations and use what I know to solve the problems I’m given.

I’ve also learned how important a supportive team can be. My first time using the fancy confocal microscope, I wasn’t very confident that I would do it right. But two of my team members were there, who offered to answer every question I had and help if I didn’t know how to use the system or something wasn’t working. My supervisor himself, if we were struggling getting something to work, would suggest that we take a water break and just have a few minutes to chat before returning to our work with clearer heads. Even though they’d only known me for a day or two, my team welcomed me with the proverbial open arms, and I never felt like I wasn’t part of the team for a single second. Something as simple as having lunch together every day made the experience much more meaningful than just getting the work done and collecting data - I made new friendships, heard the suggestions of others, and gained practical knowledge pertaining to both the lab and life in Leuven.

So, I learned it was okay to feel like I didn’t know what I was doing. Because I could trust myself and what I know to solve the problems in front of me. Where I stumbled, I could trust my supervisor and my team to be there to help and guide me, or even just make me laugh in a day full of hour upon hour of imaging cells.

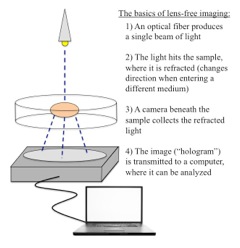

Being out of your comfort zone isn’t a bad thing in the least - it’s when you find out how much you can really do and how much you can really grow. Because of that, I’ve learned to trust my own abilities, and how important having a diverse group of people to work with can be. More than anything I’ve learned about heart cells or lens-free imaging, these are the lessons that will stick with me.

--- Rebecca Black